Text:贺瑜琦(Eugene), Prosper Washaya

Photo: Karim MD Fazlul

Video:幸晨杰(Chenjie Xing),张承康(Genesis)

Edit:李茹 (May)

>>> About the Speaker:

Dr. Tsehaie Woldai holds an MSc degree from the International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC), Enschede, The Netherlands (1976) and a PhD degree of the Open University, Milton Keynes, England (1994). Dr. Woldai is a Fellow of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS); the Geological Society of Africa (GSAF) and is the winner of many international awards. He is the founder and Past President of the African Association of Remote Sensing of the Environment (AARSE). Holding more than 100 publications, his research field is in exploration geology, environmental geology, neotectonics, geological remote sensing, radar and InSAR.

>>>About this English Geoscience Café section:

The 2nd talk of the English Geoscience Café was held from 3:00 – 5:00 pm, on 24 March 2017 in Leisure Hall, LIESMARS.As an experienced reviewer and writer, prof. Tsehaie Woldai shared his experience and ideas of the way to write a peer-reviewed paper. This speech attracted a lot of audience and triggered intense discussions.

1 Publish or Perish

"Before we start, we must think." said prof. Woldai. The way we do science has developed over 300 years, so before we start, it might be good to think about why we want to publish our work: is it really new, interesting and challenging? Is it a hot topic? Is there a solution provided for the issue we are working on? If all answers are "yes", great and let's get started!

Figure 1.Prof. Tsehaie Woldai.

For preparing the manuscript, we might want to decide on its type, identify its potential audience, choose the right journal, and then read over the "Guide for authors" of the target journal. Please remember that until your paper getting published, you are not doing science! So publish or perish? I guess you all have answers now :)

2 How to Write a Good Manuscript

There are many explicit and implied rules about making a good manuscript, but don't worry. We don't have to be great to start; we just need to start to be great instead. Following a rigid structure of scientific writing comes first. Attractive title, informative abstract and effective keywords would make our paper easy to search and read. Then comes the main text, termed IMRAD, abbreviating forIntroduction,Methods,Results,AndDiscussion (Conclusion). It should be noted that journal space is precious; our articles should be as brief as possible, and that requires a good understanding for each part of IMRAD. Each point is briefly discussed as follows according to the content of this talk.

2.1 Follow the IMRAD Rules

Introduction. There are some common rules we should follow in scientific writing, such as locating the problem we want to address, stating the originality of our work, identifying our aim and objective, and briefly describing the method how we resolve it. Besides, there are also some special tips suggested, 1) never turn the Introduction into a history lesson, 2) give the whole picture of the study area at first, 3) do not mix Introduction with Results, Discussion, or Conclusion, 4) do not repeat Abstract, and 5) Expressions such as "novel", "first time", "first ever", "paradigm-changing" are not preferred.

Methods. It might be the easiest part. Provide the readers with enough details so that they can understand and replicate your research, but do not repeat details of established methods. Readers are not idiots; they would refer to what we've cited. One tip worth noting is it would be better to organize this section with a logical storyline or procedures.

Results. One can mistake this Section with Discussion. We might want to explain what was found with tables and figures supported, but do not interpret their meanings nor over discuss the result. We might want to only present representative results, which should be further discussed in Discussion. We might want to use sub-headings and follow a logical storyline to keep this section easy to read. As for figures and tables, some tips are here to share with you: 1) figures should have brief descriptions providing readers with sufficient information about how the data was processed; 2) do not repeat the same data in both a table and a figure; 3) present the data in a table unless there is visual information that can be gained by using a figure; 4) avoid using figures that show too many variables or trends at once; 5) cite each figure or table if it is not yours; 6) Appearance Do Matter!

Discussion. It's the most important section of our article. Try to avoid redundancy between the Results and the Discussion. We might want to describe what's good as well as what's bad in our result by comparing with the literature previously cited. Remember that trends which are not statistically significant can still be discussed; it would move the body of scientific knowledge forward as well. Try to end the Discussion with a summary of the principle points we want readers to remember.

Conclusion. It would be better to provide a clear scientific justification for our work, to indicate uses and extensions if appropriate, to suggest future experiments, and to outline those that are underway. However, do not repeat the Abstract nor extend conclusions beyond what is directly supported.

Figure 2.Packed audience.

The organization of Acknowledgement and References are also important. We might want to express our special thanks to Mr. /Ms. Someone and write it in the section of Acknowledgement. The References, however, might not be such an easy thing for many writers; it is actually one of the most annoying hassles for editors. Let's strictly refer to the "Guide for authors". Try not to over inflate our manuscript with excessive self-citations or too many references: avoid which are difficult to find, which are not important/relevant to our study, or which are from the same region/author.

2.2 Learn to Advertise

Think Abstract/Keywords/Title as the advertisement of our paper! As said, an Abstract is really a brief summary (often 150 words) of the problem, the method, the results, and the conclusions, so that readers can decide whether or not to read the whole article. Try to be accurate, clear, and entice the reader to look further. Even though it is common in advertisements, comparisons are not preferred in an Abstract. What's more, we would not like to use acronyms, mathematical symbols or quantitative results in our advertisement. "Write and rewrite until flawless." As to Keywords, why not make it precise, eligible and easy for indexing and searching! Then comes the Title, which really is our opportunity to catch readers' eyes. Try to be attractive but remember that reviewers will check whether the title is specific and whether it reflects the content of our manuscript. Technical jargon and a long title would not be preferred.

3 Submit, Revise and Get Accepted!

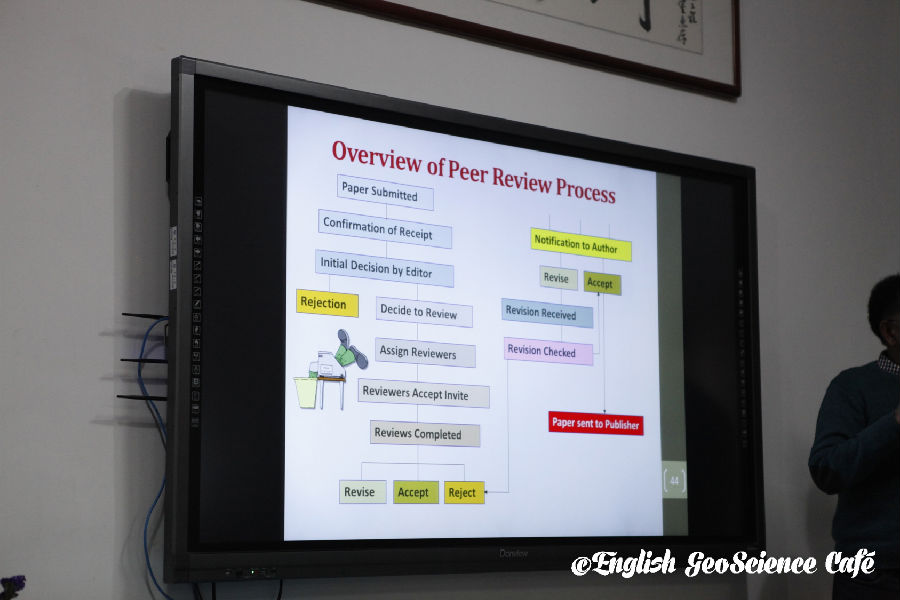

After finishing a scientific paper comes the peer review process.

Before submission, we might want to adapt our manuscript to fit the style of expected journal. Find a native English speaker (if possible) or a colleague to review the content and language, and check again whether our findings and conclusions have been reported as clearly and concisely as possible would be of great necessity.

When submitted, editors would like to check if it's original, substantial or concise enough; they will make an initial decision whether or not to review. If the answer is "yes", congrats; editors will send this article to reviewers and will get back to you some time later with reviewers' comments! Now it's time for response to these comments. When mentioning how to handle a response letter, it would be better to respond to their comments point by point, explaining what we've changed or why we didn't.

However, there might exist some reasons for rejection, including limited interest of paper, routine application of a well-known method, no novelty, failure to meet submission requirements, or unacceptability of poor English. Just take it easy if that happens; most editors will explain their decision and give comments, which are valuable for us to further revise and alternatively submit the paper to another journal!

Then Prof. Woldai continued to talk about the merits of publishing an article in an Open Access journal: our article would be peer-reviewed and published very fast; it would obtain more citations because all interested readers are free to view. Last but not the least, it is we who own the copyright to our article!

Figure 3.Overview of peer review process.

In the end, prof. Woldai shared with us an interesting ACCEPTANCE rule, which is:

· Attention to details;

· Check and double check our work;

· Consider the reviews;

· English must be as good as possible;

· Presentation is important;

· Take your time with revision;

· Acknowledge those who have helped you;

· New, original and previously unpublished;

· Critically evaluate our own manuscript;

· Ethical rules must be obeyed.

As Albert Einstein said, "A theory is something nobody believes, except the person who made it. An experiment is something everybody believes, except the person who made it." There is no room for flinch and hesitation. Why not start right now; the success could be near!

>>> Q&A

Audience No. 1:Professor again thank you for the presentation. Many of us have a problem using the reference systems. In your presentation, you briefly explained how to write a reference, but currently there are lots of reference styles like the IE, APA. My question is which reference style should we use and when?

Professor's Response:Follow the guidelines. You have to follow the author's guidelines for that journal of which you want to send, don't worry about other styles follow that one. They give exactly how you should reference.

Audience A:I have another question. When we start our paper, we should build up a conceptual framework. What areas do we have to concentrate on to give a proper conceptual framework?

Professor:Yes you need a conceptual framework. Problem definition is the solution. If you can find a problem from the beginning, it (the paper) flows by itself. Most problems arise because people start writing before finding the problem. You have to define the problem, and from the problem statement comes the aims and objectives. If you don't know what problem you want to solve then how would you go about this? The reason why I decided to tackle this upside down is because some people may advise you to start with abstract but how can you tackle it when you don't know what the problem is? Start from the point of view that you have a problem that you want to solve. Then work out the solution to the problem.

Audience B:Hello professor and thank you again for this interesting presentation. As the majority of students here I am writing a paper and I will go to revise my paper because you highlighted on many aspects that I didn't know. My question is; there are many styles and structures of paper writing, you mentioned the IMRAD style which is an extreme style and there is also the essay style which is another extreme. My question is how to write a scientific paper that can be accepted by journals with both these styles.

Audience B:My another question is: if you want to increase the chances of your work getting accepted and you submit your work to different journals, what will happen if they are both accepted?

Professor:Automatically, you get rejected. There are some people who think they are smart and they write a paper and send it to different publishers. This is considered as backstabbing someone. Some of the publishers have agreements that if something that happens they able to spot it immediately. A student sent me a PhD thesis to review, I went through the thesis. Four years after the student finishing his dissertation and graduated, I received a paper to review (similar to the dissertation) and I saw the first author, second author and the student’s name was the third. In my institution if you do that you are automatically fired, and I also rejected that paper. This is done because it is unethical for a professor to put their names first on someone else's paper. In this case the student's name should be on the top.

Professor:The first question was with regard to the different styles. I will tell you out of experience. I used to have problems with writing a paper and starting from the abstract. To give my advice, follow IMRAD and then the Abstract which is very easy. Define the problem, for example have a difficulty in using chopsticks to eat rice. That is a problem. However, if I have to start with abstract without the conclusion, then I will have difficulties. You can follow the style it doesn't matter but I encourage you to find the problem and work on it, it's the best way.

Audience C:Thank you professor for your presentation, I would like to ask about appendices because sometimes we have a lot of tables, figures and maps very useful to the paper. When should we put this information in the appendices? For example, in my paper I have a lot of tables but I can't take away some tables because they are very important and they are proof how the methodology is working in the study area. In addition, the length of the paper is limited. How can I address this problem?

Professor:I was confronted with that problem because we had a big project. Sometimes we use maps but it is difficult because for the project (in Mongolia) we had one big map which you can't squeeze into A4 because you won’t see anything. However, a solution maybe to create a summarized report and then you refer to that report if someone wants to see it.

Follow up response (from audience): I have an idea you can present your work by creating an image and present it as an image can that work or not.

Audience C:so can I include my table in the appendices and make it a part of my list of appendices? Will this count on my word count or it's excluded from the word count?

Professor:This is something you can work out with your publisher, just let them know that you have this type of table and ask them if it possible to include it as part of your appendices.

Figure 4.Questions and answers.

Audience D:I have three questions. Question number 1 how many papers should I read for me to be confident enough to start writing my paper. Question number 2 if I read a paper and find that the paper is very useful in the paper it says it has been quoted 5 or 6 times. How can I quote some's quote quoted on that paper?

Professor:Go to the manuscript and go to where they got the data, they must refer to the original paper. Unless, you cannot find that paper. If it's on the internet you can type in the address and it can tell you when it was accessed. However, I would you to go for the original quote because usually the manuscripts refer to the original quote.

Audience D:sometimes when you quote this original paper it's usually an old one but sometimes we are told to prove the relevance of our study like referring to studies and new papers. How do I go about quoting an old paper which is still relevant?

Professor:Even papers from long back can be quoted, for example Einstein's theory is from long back but cannot put Einstein's theory because it is not right.

Audience D: My third question is how can keep I track of the papers I have read and the information I have taken from papers?

Professor:A simple technique is to organize, organize, and organize. When you are writing a thesis, organize; when you are publishing a paper organize. How I do it is I create a folder then take the title of the paper and the extract of the lines that I want from the paper and attach them to the folder or you can scan the papers and use OSR to convert to word then save it. Another option is you can go to one note and keep track of your references in one note.

Audience D:I want to extract parameters from water bodies and I have twenty-five parameters. I use a table to present my data. With twenty five parameters it's also difficult for me to present on a graph.

(Response from audience): the first idea that comes to mind is you draw a map of the area and put the location on the map. The second is to quantitatively do it by putting the locations Longitude and latitude in a table and clearly state them. Another option, like in my case, is if the locations have names you can just state their names and then give links to a website where people can go and read later.

Figure 5.Group photo after this activity.

Scan the QR code below and join us!